Looking for Director Goodboss: How to Recruit a Head Librarian

True stories: An academic institution was searching for a new library director. First, the institution deadlocked because no one would break a tie vote of the search committee. When a candidate was finally chosen, it was learned that all three finalists were already being paid more than the President was prepared to offer. Then the search was suddenly stopped because the Provost resigned, and the candidates never heard anything more ever from the institution. One of the finalists learned from a commercial vendor as to who finally got the job. Two years later that person was fired and a member of the search committee told you (one of the final three) at a conference that they placed too much emphasis on one narrow aspect of that person’s record, that they should have done a better background check, and that you were that person’s first choice. Oh, and also they should have told all candidates in advance about the huge budget deficit that the director would need to overcome. Yes, it’s true. We did not make up these scenarios. Such are the experiences of many a senior library administrator on the job trail. You will find more of them described throughout this article. Suffice to say that carrying out a search for a senior campus administrator such as the library director is a costly and time-consuming endeavor that needs to be conducted properly and with an understanding of the nature of the job. Searches done poorly can result in finding no one—or, even worse, hiring the wrong person for the institution. Everyone on campus benefits when proper search procedures are followed, the right issues are addressed and, prospective candidates are treated with respect. The typical search committee will not be met with a surfeit of candidates who must be winnowed out. Rather, institutions across the country report very small pools of qualified applicants for library director positions.

The Challenge of the Search

The challenge of searching for a library director is complicated by the perspectives and stakeholder interests of the varied members of the typical search committee. Instructional faculty, campus administrators, student representatives and even rank and file library staff will lack a complete picture of the job. Given the responsibilities for budget management, personnel leadership, fund raising, campus politics, public relations, facilities planning, dealing with vendors, and incorporating rapidly changing technology, few people beyond the director him/herself really understand the job. To ensure a successful search, time and effort must be invested in educating the search committee and in effectively presenting the whole campus to the candidates. At the same time the institution is looking at and evaluating the individual applicants, that person is also looking at and evaluating the institution. “What are we looking for?” is the first question. Library Issues is heere to help! Before the search process begins, a review of the vacant position and consideration of any changes in the job description normally occurs under the leadership of the Provost or Vice President.

In the middle of interviewing for a job it became clear that the Provost was unaware the search was even going on.

Institutional leaders must articulate the qualities, talents, skills and attitudes that will be required to provide, manage and lead library services at the institution. The standard suite of qualifications listed in vacancy notices include skills in management, leadership, planning, budget, communication, collaborative decision making, staff development, fund raising, knowledge of trends in technology and higher education, and of course “vision.” Additional qualities important to the director are the following:

- Energy and dedication to the job even if it is a hard one

- A service orientation, which includes a sense that they like people

- Political skills, including an awareness of a series of interlocking structures and mechanisms (e.g., management and politics and finances within the library, across campus, the consortia, etc.)

- Awareness of the library as part of broader campus academic and planning initiatives, and of trends in higher education

- Knowledge of the “big picture” issues in higher education and libraries, but more importantly, ability to explain how those affect the specifics of service on the campus

- Creativity in solving problems and seizing opportunities

The search committee and campus administrators should be mindful of the wisdom of balancing the need for specific talents, such as fund raising, experience in building a library, or technological expertise, with the overall requirements of the position. If a person is sought who has a strong vision, then questions about resources must be answered because, in the words of University of Minnesota President Mark Yudoff, “vision without resources is hallucination.” “How should the search committee be composed and instructed?” Key stakeholders – instructional and research faculty, students, librarians and support staff – should be represented. The importance of technology virtually dictates the inclusion of a social network or computing services officer. Institutional politics, priorities, problems, plans, demographics and traditions will shape the remaining composition of the committee. A high priority on fund raising might result in a development or foundation officer on the committee. Need for a new building may result in a facilities management representative. At the same time, appointing faculty passionately concerned about the library may risk their coming across as “single issue” interviewers. Care must be taken to stock the committee with balanced views and informed judgment. Beyond the basic “charge,” it is advisable to provide the search committee with information, insight and advice about contemporary trends in library and information services, and about the role of the library director. The library’s staff may not have a comprehensive understanding of the director’s role. Therefore, bringing to campus one or more directors from similar institutions to review, advise and consult with the committee can provide valuable insight. Even including the local public library director on the search committee or in the formal interview process can be informative. At minimum, a brief reading list of recent articles, Web sites and information sheets, together with recent planning and program review documents, assembled with the help of library staff, can assure that all committee members start from a common base of knowledge.

“What kinds of candidates are appropriate?” Some recruiters may seek a director from an institution of similar size or mission. However, the size of staff or budget previously managed may not be the most relevant part of their experience. Searchers should not overly fixate on the fact that the candidate may come from a different size or type of institution than the one involved in the search. The role of the library director does not differ greatly from college to university. The role of an assistant director may be different. Do not assume that the assistant director, whether from a large place or small, sees all the issues and challenges that the director handles, or that assistant directors are naturally poised to be directors. A director from a different type of institution may be more comfortable in the role than an assistant director from an identical peer institution. Very important is the director’s ability to function politically in the local campus culture. When library directors are let go a year or two after appointment, it’s usually because they did not understand the culture, did not learn how decisions are made, and offended those with power and influence.

The candidate did not list any references from his home institution and the committee did not seek out anyone. The faculty members of the search committee were very impressed with his PhD from a prestigious institution and his record of scholarly publication. After he was hired, it was learned that he had been asked to leave his previous position because of nonexistent management skills.

The search committee must be clear on whether to require, or to what extent to “prefer,” a doctoral degree. The Ph.D. is not viewed as the terminal degree in the library profession. Making it a mandatory requirement is likely to diminish an already small pool and may attract applicants with a doctorate but with less useful experience. A heavy preference for it may override critically needed skills and talents of Masters educated candidates. The same cautions pertain to requiring an extensive record of research and publication. The structure of the library and its place in the institution – possibly merged with IT or the museum or the university press – may dictate the consideration of candidates beyond the library field or beyond people working presently in academic institutions. Be prepared for controversy, however, if candidates are considered who have no degree in library science at all, or who have not held senior positions in libraries. While this may work in some situations, it must be carefully thought through. Is the present staff strong enough to keep the library running on a day-to-day basis while the new director is learning? Will the staff persist in questioning or resenting a director who has not earned the MLS “union card”? Academic libraries today require major management and strategic skills in the context of specific issues and trends. The search committee and the superior officer should reach accord at the beginning of the process regarding the priority relationships among all desired attributes.

“How should we search?” The usual process is to place vacancy announcements in leading academic and library publications and electronic lists, and then delegate the searching and screening to a committee. The chair of the search committee should be in regular and frequent contact with the officer to whom the librarian will report, and also with the Affirmative Action office. This continuing contact will keep the search on schedule and assure that both the committee and the administration are agreed throughout the search process about the priority of skills sought, definition of terms, deadline dates, and proper protocol.

A candidate was invited to apply for a directorship at the last minute, and asked if it was OK to supply the vita from his web page (the only place where he kept it up to date). He was assured that that was fine. A year later he found out that he did not make the final stage because an English professor on the search committee was offended by the informality of the vita.

Members of the committee need to have clear explanations as to how applications are being received, by whom, when and how they will be circulated, and whether there is a final cut off date. It is not unusual to have a committee where few members have been involved with this kind of search, and it is all too easy for them to be unintentionally careless in ways that may jeopardize the search, by antagonizing a good candidate or even committing legal errors.

A hired headhunter informed the candidates he called that the job was a great one, easy to do, just kick back and don’t worry. Good candidates were not interested in applying, and in fact were insulted by the headhunter’s lack of knowledge of what is required to manage a large research library.

A headhunter may be hired to assist with the search. This can provide experienced professional guidance for the search. Among the headhunter’s valuable services are training the members of the committee in “search etiquette,” pre-interviewing, helping to package appropriate background documentation on the library and institution, and helping to promote the vacancy more widely and actively. Some headhunters prescribe a standardized resume and application format, but this may eliminate a valuable insight into the presentation style of the candidate. When using a headhunter, there is a risk that an overly corporate style will be projected, so the institution should make every effort to convey to candidates that the academic leadership of the university is ultimately in charge. Candidates should, for example, be invited to speak with the chair of the search committee if they have questions. Also, formal interviewing should be conducted by the committee.The pool of qualified applicants for library director positions is often quite small. Search committee members and the chief academic officer may need to take an active role in recruiting, beyond basic advertising. Calls to colleagues at other institutions that have recently completed director searches may yield names of good candidates who were also-rans. Library leaders in major libraries, national associations, and foundations are usually in touch with or aware of active directors and assistant directors and may know who may be good prospects for a given institution.

Invite, Interview, Investigate

Invitations to the interview open a new phase of the search process. The institution now begins to be investigated and scrutinized by the candidates. The invitations and the advance information provided to candidates are the first impressions made by the institution. If those impressions are poor ones, a very good candidate may choose to withdraw. Relevant, accurate and extensive information provided in advance will increase the odds of a mutually informed interview. Institutions may wish to err on the side of providing more rather than less information, and should not be shy about sending five pounds or more of catalogs, accreditation reports, annual reports, and community information. Be wary of candidates who do not appear to be interested in advanced information.

Members of the search committee indiscriminately and without notice telephoned members of the candidate’s support staff, and then repeated unfounded rumors about the candidate and his wife. One candidate’s resume stated that she had been a U.S. Congressional Fellow. When this was checked, it turned out that in reality she had served as a volunteer for one week in her congressperson’s office.

To respect confidentiality, the pre-interview reference checks should be limited to persons whom the candidates have listed as references. Candidates from a small place may not wish to have it made public that they are interviewing for another job, even at a much more prestigious institution. Directors’ credibility and effectiveness at their current institutions can be quickly eroded if they are known to be out looking. Contacts beyond those references listed by the candidate should be made only when a very short list is assembled, after preliminary screening, and only after asking the candidate. Throughout the search, be aware that the academic library grapevine is fast and far-reaching and will rapidly spread information—accurate or not—about the institution and the candidates. Continuing contact with all candidates until after they are notified that they are out of the running can preempt questions and avoid confusion and uncertainty. Acknowledge every letter of application, reminding the candidate of the required elements of the application, who is to provide them, and how many have been received with the letter (or e-mail) of application. Inform candidates if the search is extended, or if the library director’s superior suddenly resigns and the search is placed on hold. To assure the accuracy and consistency of communication, it would be wise to have all questions addressed to and answered by the chair of the search committee. In many cases a committee will want to do a first round of interviews. These should be more confidential and may be held by phone, videoconference or even off campus for logistical convenience. Final interviews should include as many of the library’s stakeholders as can be scheduled. The more feedback that is obtained, the more informed the selection decision. And the more people the candidates meet, the more accurate their impression of the institution and its library. A tour of the Library and meetings with all library department heads, is a minimum requirement. Open fora with library staff and also with faculty and students are helpful in gauging a candidate’s performance in a group setting, especially in response to rude, inept or uninformed questions. A candidate’s questions are often more informative and revealing than the candidate’s answers. Interviews can be aided by building upon lists of questions available in the campus personnel office. Careful attention must always be paid to Affirmative Action and EEO guidelines. Questions that probe the candidates’ creativity and flexibility in dealing with people, problems, change and the challenges of reaching goals should be the most important questions asked.

In the open forum, rude faculty collaborated to wear down and smoke out the candidate. Staff members asked loaded questions related to ongoing grievances that forced candidates into giving contradictory answers to different groups.

Questions that put the candidate on the defensive, such as “isn’t this job a big leap from where you are now,” don’t really help the committee see how the person thinks. Better ways to elicit management, leadership and political skills would be to probe the complexity and structures that the person is accustomed to managing, and then gauge the candidate’s success in navigating the politics of that environment. For example, such things as the number of levels of supervision, the number of branch libraries or special collection units, experience with reorganizations or downsizing on campus or in the library, the nature of direct reporting relationships, relationships with colleague directors outside direct report lines, and communication and governance mechanisms within the library. Regarding budget, helpful questions include the number and different kinds of budget categories (rather than exact dollar amounts), how many different kinds of funds (current, endowed, grants, etc.) must be managed, how the collection development and information access budget is generally allocated, and how the candidate has creatively moved funding or budget categories to be able to initiate new services or deal with cutbacks. Other topics of inquiry may include the following:

- relationships with faculty on campus

- relationships with other campus administrators (student services, physical plant, human resources)

- experience with facilities planning (new buildings, renovations, storage, etc.)

- experience in library and/or educational consortia

- experience with development

- approach to external community relations

- strategies used to ensure effective collection development (print vs. electronic, mix of subjects, local vs. remote, etc.)

- examples of specific personnel problems and how they were resolved

- examples of innovations in services or projects

- examples of campus-wide committees or projects, not necessarily library related, in which the candidate has been involved.

Presenting the Institution to the Candidate

Many times, the campus is not presented effectively to the candidate, who will be observing how well your institution has its act together. The candidate should not be left wondering who is supposed to pick them up and escort them to meals and meetings. The candidate has to get a good feeling from the whole campus, not just the library.

The faculty library committee never showed up for their part of the interview schedule.

Some candidates have been kept waiting so long by one dean that they had to leave in order to make it to the next event on the schedule. Others have been assailed by faculty who believed it proper to subject the candidate to controversial, penetrating and insulting questions, intending to see how the candidate holds up. Sometimes a candidate has no meetings with any of the IT people. The fact that the library has its own network staff is not a good excuse for this oversight in this era of converging technologies. If things aren’t going well in the library, the search committee may become a lightning rod for everyone (staff, faculty, students) to vent their frustrations. This may or may not be an accurate picture. Instructional faculty need to avoid dominating the interview process with their pet peeves. Expectations of a new director may be unrealistic. Nevertheless, the issues must genuinely be conveyed to the candidates, because the successful candidate will be facing that environment.

Internal Candidates

The assistant director, who was an internal candidate, sat in on library staff interviews, as did a former director demoted some years ago.

If there are internal candidates, including them in the interview process not only inhibits the free flow of questions and answers from other institutional participants, it may provide an unfair advantage. Internal candidates can be the first to be interviewed, or can be on leave on the other interview days. If there are none, it would be encouraging for candidates to know this at the time they are invited to campus. Former directors still present on staff or on the campus and participating directly in the interview can have a similar dampening effect. Institutional representatives must be prepared to answer honestly the question of how a new director would be able to manage and lead with former incumbents still resident at the institution.

Final Checks after the Interviews

Candidates who survive the interviews should be subjects of final reference checks, especially a call to the current supervisor and perhaps to a key subordinate. It can be awkward but everyone in this situation should be prepared to expect it, or to have a very good reason for why people cannot be called. Deans and directors in all offices on campus can be asked to network confidentially with their peers at the candidates’ current and former institutions. Such background network checking should be able to penetrate any “conspiracy of silence” erected by another institution in order to help a poor performer make the earliest available career move. Telephone background checks at this stage should be only those authorized by the library director’s prospective superior. Indiscriminate telephoning of anyone by anyone risks puts both the institution and the candidate at risk from confusing or inaccurate information.

Digging for background dirt, follow-up telephone calls were made to past colleagues without the candidate’s knowledge or permission. Elsewhere, a provost abruptly decided that no checking was needed because the candidate was a personal acquaintance.

Following up after the Decision

As soon as applicants are eliminated from consideration, common courtesy requires that they be informed. Applicants and candidates have lives to lead and other career plans to make. Recruiters should keep them as informed as they themselves would wish to be. The hiring institution makes a good impression by telephoning all of the interviewed finalists as soon as the final hiring decision and agreement are made. Library staff and internal candidates should be informed before the decision is generally announced on campus. Campus administrators and faculty leaders in the senate, et al., should also receive the news before reading of it in the campus and city newspapers. Some words of support and context should accompany the general announcement if the decision is thought to be controversial.

Final Thoughts

No search process is perfect. Search committees are composed of human beings who do not always have the insight or leadership to make the right recommendation for the institution. Provosts and vice presidents need to be free to exercise their own judgment and not take the easy way out by going along with groupthink and committee consensus. In the end, any investment in a new library director is as much a gamble as an investment in the stock market, and is just as subject to unpredictable and unforeseen developments. As with financial investments, the personnel investment in a new library director is best served by timely and accurate research and by carefully considered efforts to fit perceived talents to known needs and desired goals.

Recommended Book

Academic Librarianship is a comprehensive book by authors with extensive experience in academic libraries. In it they look beyond management in libraries, since many texts and courses cover this aspect, and focus instead on the academic library environment as a whole... With plenty of information packed into the pages, this book is a must-read for anyone working in an academic library.

Latest Posts

- Google's Digitization Project — What Difference Will it Make?

- Assessing the Library’s Contribution to Student Learning

- Shaping a National Collective Collection: will your campus participate?

- Looking for Director Goodboss: How to Recruit a Head Librarian

- Social Networking: Strategic Use and Effective Policies in Higher Education

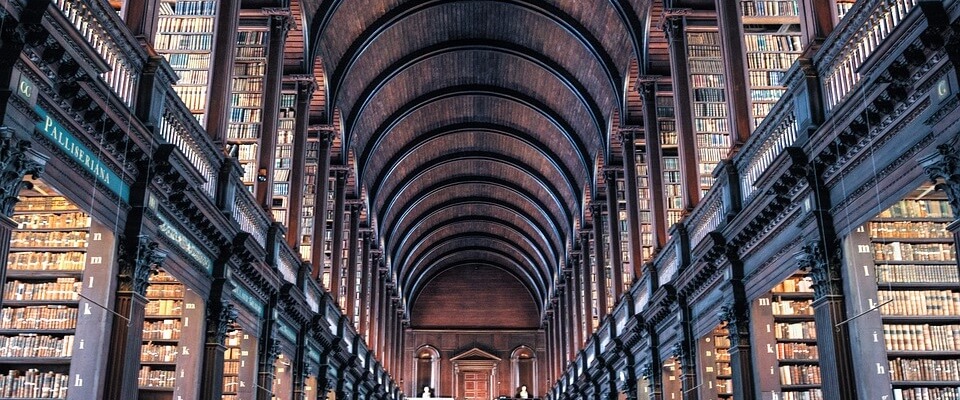

- The Library as a Place: Tradition and Evolution

- The USA Patriot Act: How Will Your Library Respond?

- What Good Are All These Links? Rethinking the Academic Library Website

We are part of PLA

Copyright © Library Issues. All Rights Reserved